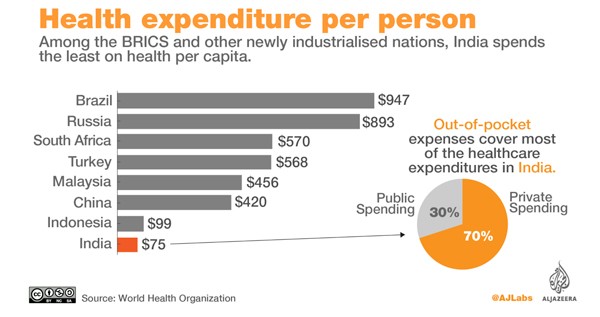

Figures widely published in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic in mid-2020 said that the Indian government’s spending on the health sector in FY 2018-19 was 1.5% of GDP. Other figures published at the beginning of 2021 say that the government’s health expenditure is even less at 1.26% of GDP. In the government’s 2021 budget, India’s public expenditure on healthcare stood at 1.2% as a percentage of the GDP.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization says that the Indian per capita expenditure on health care expenditure is currently 3.54% of GDP and that this includes 62.67% out-of-pocket expenditure by citizens. In other words, the numbers seem to tally and are abysmally low. In mid-2020, various experts such as the Niti Ayog member for Health, VK Paul, suggested that the country’s overall spending on the health sector is low, and the situation must be ‘corrected.’

The National Health Mission document says that the expenditure on the sector should go up to 3% of GDP by 2025. Paul suggested that the government should target the primary healthcare sector and that the private sector could focus on the secondary and tertiary levels. He said that medical colleges increased by 45% in the preceding six years, accompanied by an increase of 48% undergraduate seats for medical students. He suggested that the postgraduate medical seats had increased by 79% and forecast the building of 114 new government hospitals in the next three years.

A more recent article by Ashwini Danigond published in May 2021 in The Hindu Businessline suggests five main reasons why India’s healthcare system is struggling. First, Danigond suggests, “There’s a need to make people and processes in the healthcare sector made more accountable – for that, greater operational transparency needs to be brought in urgently.” Another reason he cites is the low number of institutions and the ‘less-than-adequate human resources.’

Ironically, none of the experts, critics, and soothsayers point out that even with limited educational facilities, Indian doctors and nurses represent a good number of the front-line healthcare workers in the Middle East, Europe, and America. Public and private hospitals and national health services, and private practices are increasingly populated and run by doctors, nurses, and administrators from our country. The country’s medical education and on-the-job training in its institutions seem adequate for migration and eventual expertise and pontification on television channels and even UN organizations.

Danigond points to the complexity of the issue – that medical personnel must be paid better. That healthcare must move from reactive to pro-active care. But, he says, “The situation remains worrisome in rural areas, where almost 66% of India’s population resides. The doctor-to-patient ratio remains abysmally low, which is merely 0.7 doctors per 1,000 people. This is compared to the World Health Organisation (WHO) average of 2.5 doctors per 1,000 people. Improving this situation continues to remain a long-term process.”

Danigond also, in my view, quite mistakenly points to health insurance as a solution, “A possible solution to address the issue could be to increase the adoption of health insurance. In this regard, the government and private institutions both need to work together. Adoption of digital insurance processing solutions integrated with the healthcare ecosystem for faster turnaround time for insurance processes will also motivate adoption of health insurance.”

More to the point, he says, “What primarily ails the healthcare system is that there has been a general lack of focus on the vertical from the government.” This is really the issue in my view. The government does not see education or health as its obligations, although stated in the constitution. It believes in the privatization of both education and healthcare. If anything, it sees its role as providing low-cost assets to private industry in the form of subsidized human resources, infrastructure, and land. The public institutions must remain starved to feed both migration and private institutions since the two are related and helpful in bringing foreign direct investment to these sectors.

There is no thought of building world-class clinics, hospitals, research institutions, and scholarly and scientific publishing in rural or metropolitan areas. The ministers can continue to go overseas for treatment and transplants funded by public money. There is no thought of creating a vibrantly engaging environment for the best talent that the country has.